Key points:

- Over the past decade, canola planted acreage has increased in the northern Great Plains.

- Increased interest by producers likely reflects both economic and agronomic/disease management factors.

- If pulse production continues to grow in the NGP and spring wheat prices return to normal, continued land allocation to canola and other oilseeds is possible.

As my colleague Kate Fuller astutely pointed in a previous post, several fields near my house were planted into canola this year. This is the first time in years that I’ve seen anything other than small grains in those fields. Then, a few days ago, I was asked to provide some thoughts on potential growth of canola production in North America. All this made me wonder: what the heck is going on with canola?!?

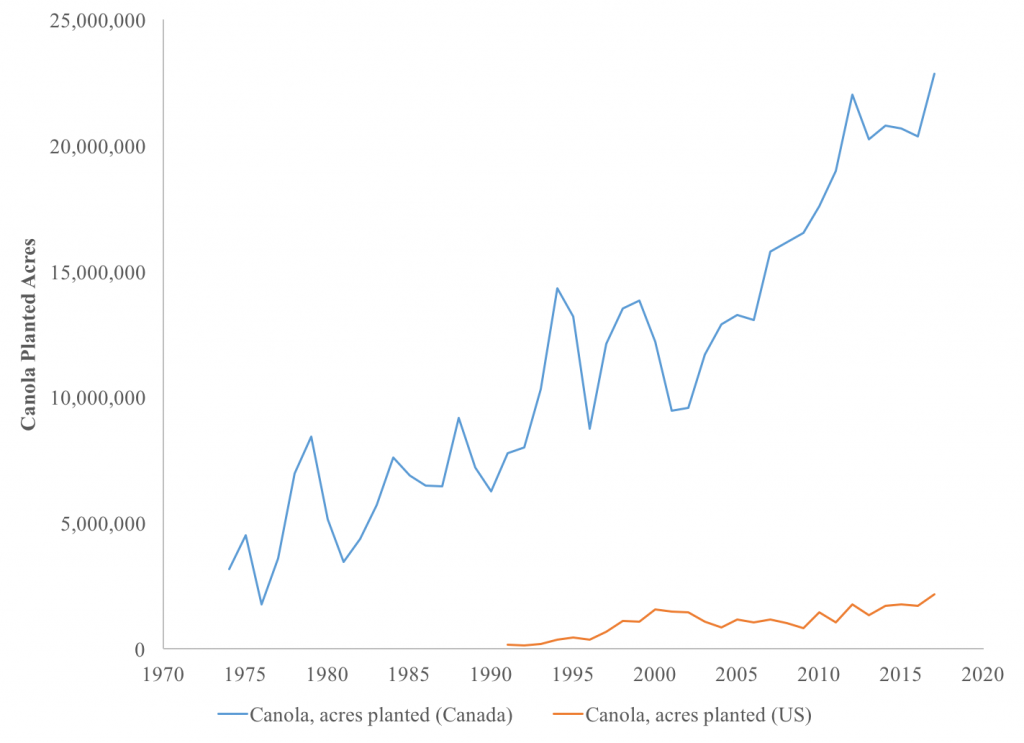

While Canada’s canola production has been increasing steadily since the 1970s, I was pretty certain that the United States’ oilseed of choice was soybeans. But, as the figure below shows, there does seem to be a consistent uptick in canola planted acres within the United States. And the table immediately following the figure indicates that the northern Great Plains have been a major contributor to this growth.

| 2017 Planted Canola Acres | Trend since 2009 | |

| Idaho | 25,000 | 38.30% |

| Minnesota | 30,000 | -6.81% |

| Montana | 130,000 | 398.18% |

| North Dakota | 1,700,000 | 59.23% |

| Oklahoma | 160,000 | 105.41% |

Data sources: Canadian data are from StatCan and U.S. data are from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service.

So, what could be affecting this growth? Well, economics certainly is one likely culprit. One of the factors that goes into a farmer’s land allocation decisions is the relative price of one crop to other crops that could also be grown on an acre of land. If a producers observes the price of one crop being relatively higher then the price of another, they are more likely to consider planting the more valuable crop (all else being equal). But does this relationship hold for canola?

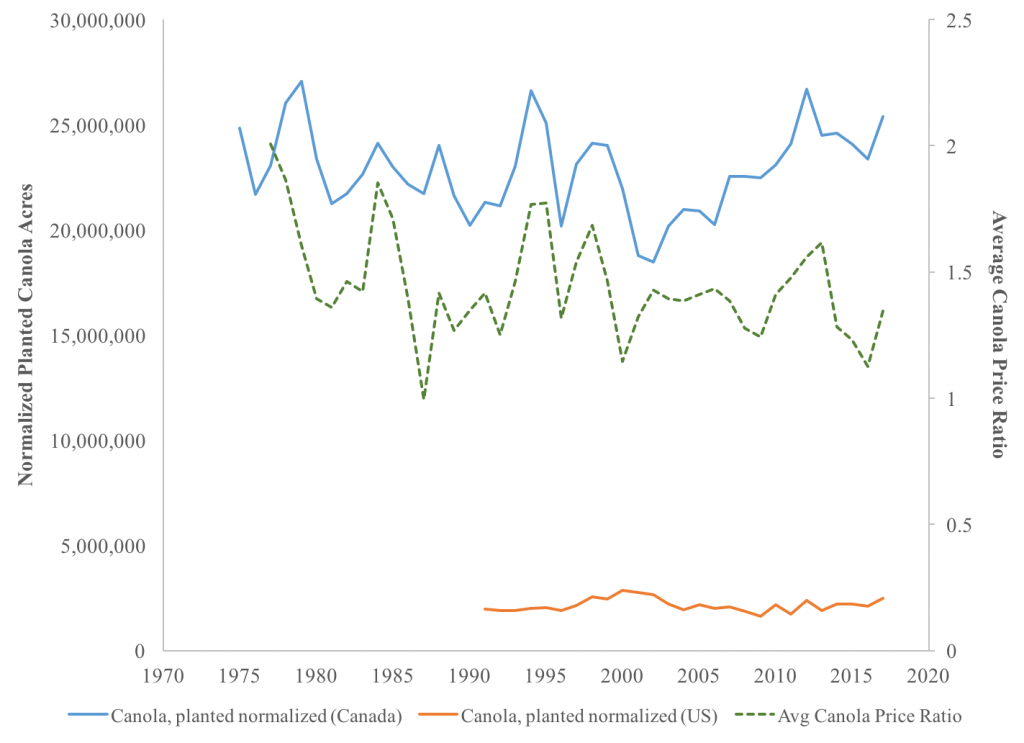

The figure below again shows planted canola acres, but I removed the trend so that it was possible to compare planting decisions across different years. This is similar to adjusting for inflation in order to compare the price of 1 bushel of wheat, for example, in 2017 to the price of a bushel in 1950. So, the figure shows how planted acreage varied across years with 2017 as the base year for comparison. Additionally, the figure shows the average price ratio (green dotted line) between canola and four competing spring crops: spring wheat, soybeans, lentils, and peas. That is, the green line shows the average relative price (value) of canola compared to the prices of the other crops. But, I only limited these prices to the March–May period of each year.

In other words: the figure below shows the relationship between relative crop prices that producers observed at the time when they made planting decisions and the resulting planted canola acres in that year.

The figure makes fairly evident that in years when the price of canola was relatively higher than the prices of the other competing crops during the March–May planting decision period (i.e., spikes in the dashed green line), we also observed higher canola planted acres (i.e., spikes in the blue and orange solid lines).

In addition to economic reasons, northern Great Plains farmers are also likely looking to canola for disease management properties. With the boom in pulse production in the northern United States, there has been increased concerns of disease pressure associated with overly aggressive pulse–wheat rotations. Many experts recommend at least a three-year rotation when planting pulse crops in cereal systems, and in the semi-arid, drylands production practices of the northern Great Plains, canola has seen increased interest from producers.

Of course, at $7.00–8.00 per bushel spring wheat, most crops will have difficulty competing for land allocation next year. But, if pulse crops continue to be a solid player in the NGP production environment and spring wheat prices return to historical averages, fields of yellow may become a much more prominent feature of the northern U.S. landscape.

Have you thought about or started to grow canola? What were your reasons for starting? What have been your challenge or successes so far or what do you envision as advantages or drawbacks to canola production?

(Photo by _TC Photography_ is licensed under CC BY 4.0)